|

March 1st, 2004 -

Day breaks upon a world so barren of freedom

-Youssou N’Dour

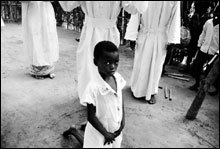

Looking at the pictures of Kinshasa, the war-torn capital of the

Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), displays before you stark scenes

against which pictures taken in Baghdad make it appear as if the

Iraqis live in the midst of peace and plenty. Buildings look beat

up and tired, and the streets don’t look at all like the ones

in Manhattan. The locals just survive from day to day. With an average

life expectancy of around 50 years, life for the average Congolese

is short, devoid of liberty, and brutal.

Trying to eke out an existence in the midst of all the squalor,

violence, and poverty, live approximately 40,000 Congolese street

children. They are not there due to the war; they are there because

of their parents.

Finding the Witches

BEDEVERE: Tell me ... What do you do with witches?

ALL VILLAGERS: Burn them! Burn them! Burn them up!

BEDEVERE: And what do you burn apart from witches?

FIRST VILLAGER: More witches!

-From the movie “Monty Python and the Holy Grail”

The latest horror that the Congolese people have gotten into is

that they are accusing their children of being witches and either

killing them or casting them out into the streets. This has gotten

so prevalent that according to UNICEF and the UN there are anywhere

between 15,000 to 40,000 children, mostly between the ages of 3

and 13, living on the streets of Kinshasa.

Now this is an approximation, since the DRC exists in a Land of

the Approximate. Nobody really knows the true number, and God only

knows what goes on in the rural areas or the completely anarchistic

eastern part of the country. The street children do not stand out

among other Congolese because of their suffering. Except for the

few strongmen at the top, everybody suffers in the Democratic Republic

of Congo. It is the children’s age and the fact that it was

their own parents who put them in this bind which sets them apart.

Human beings have always taken pleasure in abusing each other; but

it is rare to see parents abuse their own children to such an extreme.

From the day they’re accused of witchcraft, the children struggle

to survive – parentless - in a country devoid of anything

resembling the rule of law. The rule of man holds sway over the

DRC. Consequently, Congolese life is chock full of arbitrary adult

cruelty and the children are not immune as targets. Additionally,

since the average Congolese man on the street most certainly does

believe in witches, these children can expect little if any help

from the adult world. And that is about what they get.

A special fear for all Congolese children is the cult “pastor”.

The pastor is a lethal combination of medicine man, high priest,

and judge. They will approach families and offer to “cleanse”

child witches for a fee. He also operates in the opposite direction,

fingering a child as a witch, placing the child in immediate danger.

Parents also seek out such men, looking for someone to give them

support for the witchcraft accusations against their child or a

cure for it.

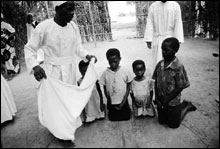

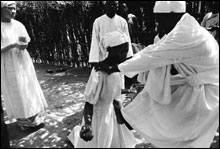

In order to see one of these pastors at work, we traveled by jeep

one hundred miles from the capital to the village of Kinsiona. There

we were led by our translator to a rude structure constructed from

branches and leaves. Inside, among a curious crowd, were a pastor,

his two assistants, and four small child “witches”.

Upset at our presence (and being part of an outlawed cult) the pastor

and his two assistants refused to give their names. Yet the head

pastor allowed us to stay and take numerous pictures. So I doubt

if given the chance he’d build much of a criminal empire.

But he had brains and authority enough to have four small children

on their knees before him awaiting his judgement.

The children (who had already been accused of witchcraft) knelt

on the dirt floor in front of the pastor. He performed various rituals,

what they were is of no importance. The fact that all involved believe

that the children are in fact witches is of the utmost importance.

The pastor also performed some rituals on the mother, such as placing

his foot on her sexual organs to make sure that she would not bear

anymore witches. While you might chortle over your breakfast at

people believing such absurdity, make no mistake that many Congolese

most certainly do believe it.

After all was said and done, the pastor claimed that “more

work” (and hence more money) was needed to cleanse these witch

children. The parents left with the children in tow. Being impoverished,

they might very well decide to part with their children rather than

their money.

According to many reports, Congolese parents use the accusation

of witchcraft as a pretext for ridding themselves of an extra mouth

to feed. No doubt this is true. But no doubt it is also true that

many do believe it. Either way, thus grows the ranks of Kinshasa’s

street children.

Children R’ Us

Just a’ urchin living under the street.

Guns and Rose, “Paradise City”

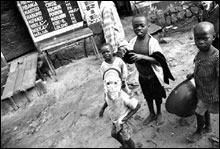

While in the capital, we used our contacts to be introduced to

a gang of street children lead by Bigassa, a 25 year old man. He

is a five year veteran of the streets and plays Fagan to about seventy

or so Oliver Twists. Bigassa ordered one of the older children,

a 16 year old street veteran dressed in an Iron Maiden tee-shirt,

to perform escort and protection duties.

The gangs of Kinshasa are not like the ones we see in America. No

chest pounding macho names, color coded clothes, or days spent hanging

on street corners for them. They are much poorer, to get food requires

much time and effort. Some street children have odd jobs, but with

the social stigma they live under it is not easy to find one. (Kinshasa’s

moribund economy is not creating many, anyhow.) A day without food

is not unusual for these children. Many of the children are not

near the same height or weight as American children of a similar

age; mal-nutrition and disease (particularly malaria) are common.

You do not see obese people in Kinshasa.

Unlike America’s gang children, who usually have at least

a mother in their lives, these children are bereft of any discipline

or parental authority at all. Consequently, by the time a street

child hits 15 or 16 he is by all accounts irretrievably lost to

a brutal code of violence. The older children are much feared, and

with good reason. Within a week of our arrival four policemen, armed

with AK-47s, were ambushed and massacred by a gang of children.

They had ventured into the Cemetery of Gombe in Kinshasa’s

former European quarter. It is well known that at night the cemetery

belongs to the child street gangs – one enters at great risk.

The children have become a “social problem” far beyond

the ability of the government to handle. If they even cared to,

that is.

Children from the local area do not venture far from the homes that

they used to live in. With the social stigma of being a witch hanging

over their head, though, home might as well be on another planet.

It is in their past, irretrievable. They band together as much out

of necessity as out of a need for companionship. It is much easier

to survive as a group than as an individual. The gang is usually

led by an older, more experienced child. With the societal breakdown

bought on by the civil war, the cases of witch accusations have

taken a corresponding upturn. The children have many companions

to choose from.

There are female as well as male children. The females have an advantage

– if you could call it that – in that they can sell

their bodies. Child prostitution is common among them. Age does

not seem to be a barrier to entry, girls as young as five are reported

to be selling themselves for money.

Bigassa’s gang escorted us throughout Kinshasa, allowing access

to a part of their world. We saw them sleep upon the ground at night,

bathe in filthy alleyways, and try to obtain food. The children

displayed the wondrous curiosity innate to children everywhere.

The children, especially the older ones, are prone to violence;

they know of no other code. This trait does not make them stand

out in a country like the DRC. Amigo Gonde of the local rights group

Asadho recently said that, “there are many places in Kinshasa

where street children are violently dealt with”. Like all

survivors in such a place, they must give as well as take.

The children live day to day. Endless searches for food, avoiding

government forces, and dealing with the social stigma of being a

“witch” constitutes their existence. They dream no dreams

of a better world, survival takes up all their time. As Nadine Giese

(a local child activist) stated, “for them, the real struggle

is just to live another day”. And that’s about all.

The Oasis

Beautiful flower in your garden, but the most

beautiful by far,

Is the one growing wild, in the garbage dump,

Even here we are.

-Paul Westerburg

There are a few glimmers of hope for the children of Kinshasa’s

streets, one such comes from an organization centuries old –

the Jesuits. It is the Center Monsieur Munzihirwa, located in Kinshasa’s

Cite area. Run off of donations from the outside world (which, when

you come to think of it, is pretty much how everything in the DRC

runs) the staff of five provides fifty beds and fifty long shots.

The staff caters to the street children of their locale, offering

food, a bed, rudimentary education and, most importantly, a chance

to go home. This is where we found Luzizila, a 13 year old boy.

He had been living on the streets for two years when the center

found him, and had been living at CMM for a few months when we arrived.

He had been thrown out of his home by his parents after they accused

him of being a witch. Like all his cohorts, Luzizila was mal-nourished

and had stomach aliments from eating poor quality food. Thoroughly

acclimated to the streets by this time, he was still young enough

to warrant CMM’s gambling on the possibility of his re-entry

into society and family. Once a street child reaches the age of

sixteen, by all accounts they are hopelessly lost to the street.

Due to the rigors of life on the streets, the older children are

physically similar to American children five to six years younger.

Though he was thirteen, if you saw Luzizila in your local shopping

mall you would very likely guess him to be about eight. He does

have a distinguishing feature to his benefit – he’s

cuddly cute to look at. Luzizila is a born poster boy for every

NGO’s donation brochure.

The children at the center, under the head of Father Bakwem, have

a fixed daily schedule. All must attend class, all must perform

chores, all must re-learn the habit of self-discipline they had

lost in their time on the streets. The center, with a staff of five,

is desperately trying to re-create one hundred missing parents.

It’s a long shot at best.

In addition to taking care of the children, the center also attempts

to locate the actual parents – not an easy thing to do in

a war torn nation. For Luzizila, it was not that difficult. He had

not wandered far from his parent’s house – in fact,

he lived in the same area as they. Once a child’s parents

are located, the school invites them to classes where they try to

convince them their belief in their children being witches is irrational

and cruel. If it isn’t enough to make the parents agree to

take the child home, they also offer to pay for the child’s

schooling for one year.

Should the parents accept the child to return, the school will continue

to monitor the home for one year to check up on the child. What

happens after that is anyone’s guess. There were no records

of “success” rates, no idea on how many of these children

wind up back on the streets. CMM’s work is a mixture of much

effort, earnest prayer, and blind hope.

Luzizila’s parents agreed to take him back.

On the day Luzizila was to be re-integrated with his parents, he

looked decidedly less than happy. The past two years had undoubtedly

been a horror for the child, the Jesuit center no doubt seemed to

him an oasis. Now he was to leave, and return to the very source

of his troubles – home. His father was not there to greet

him, his mother looked uneasy and ashamed. She seemed none to happy

about having another mouth to feed again. According to Nadine Giese,

who works at another such center for children, the parents “often

use sorcery as a pretext to get rid of them”.

Where Luzizila will be in a year – or where he is right now

– is in microcosm the plight of the DRC. Cruelty, arbitrary

rule, and irrationality are in abundance. Even should he be permitted

to stay home this time, what chance for a future does he have in

such a nation?

“The extreme of folly, wickedness, and absurdity

in the mores is witch persecutions, but the best men of the seventeenth

century had no doubt that witches existed and that they ought to

be burned.”

-William Graham Sumner

Before we get all smug over how much better human beings we are

than the Congolese, we well fed Americans should not forget that

only 350 odd years ago strapping a female “witch” to

a wooden stake and setting her on fire was considered by many of

our forefathers to be a perfectly logical thing to do. To believe

that New York City could not one day be in the same situation as

Kinshasa is to deny our own humanity.

Within our Western world, the century just past gives us an example

much like what we see now in Kinshasa. In communist Russia (last

century’s “progressive” ideal), children left

orphaned by government attack on their parents were so numerous

and created such problems for public order that state security forces

conducted mass raids in Soviet cities to round them up. These children,

known as besprizornye, were, like the street children of Kinshasa,

deeply feared by others for their violent dispositions.

When Stanley left the Congo in 1872 after his quest to find Livingston,

he described what he left behind as “horrors”. Unfortunately,

nothing much has changed with the Congolese people in the interim.

Despite all our best wishes and money, nothing will change unless

the Congolese people themselves institute the rule of law. Until

that time they will continue to suffer endless repetitions of what

they are going through now. And their children, the weakest and

most vulnerable of their people, will suffer most for it.

|

|