An interview Conducted by Alejandro Dorado Nájera (@DoradoAlex) and Diana Lopes

Mozambique has one of the biggest growth potentials in the region and even in the world. Even now, while facing economic challenges, there is still economic and cultural potential in the country. Having been president for many years (1986-2005), in your experience, what steps should Mozambique take to make good use of this potential, in order to further consolidate its position as a regional leader?

The first step would be the continuous mobilization of all living forces of the country to engage in sustainably exploiting the natural resources and, of course, the existing human resources; developing their skills by the initiative of the government, so that they can develop themselves. The men and women are the first and the greatest potential of the country, as they are people who like to learn and work. They, however, need more guidance, that can be acquired through a process of study and learning, but also with the progressive improvement of the different leaderships, both in the government and in the private sector. This is the first source of potential.

The second source of potential are the natural resources, which depend on human resources, starting with agriculture. Agriculture has always been defined as the foundation of the Mozambican economy, and I think it will continue to be for a long time. Agriculture must undergo some changes, regarding the manner in which it is practiced. We must not only produce agricultural products, but also to include components of its transformation. Farmers should be involved in the value chain. It is necessary to break the myth that “those who want to die poor must be farmers.” If we develop agriculture in the sense of diversifying, adding value to the products and so on, the farmer can be as rich as other workers.

In Mozambique, we have immense wildlife resources; flora and fauna that must be well managed. I believe that, one day, tourism will be a major industry in Mozambique.

We still have a very rich subsoil, which is still barely explored, unfortunately. Various ores such as gold and phosphate, among others, have been discovered. Lately, the resources that are found to be of greater value and quantity are coal, gas, heavy sands, and oil.

These are the sources of potential that the country has and the way I see them.

Mozambique has, in recent weeks, filled the pages of the international newspapers with news related to EMATUM and its debt, the downgrading by rating agencies and the controversy with hidden loans of other public companies and the IMF. His Excellency knows the consequences that a bad international image may have for a country in terms of perception and trust. What measures must be taken in terms of image reconstruction and the Mozambique brand abroad?

We have to correct the procedures that were not followed. Due to the volume of the debt, the IMF and the Parliament should have been informed about it.

What pleases me is that the government is acting in a calm manner, facing the situation, opening-up the entire situation as best as possible. It is a government that does not hide behind the fact that these agreements were made before, by the previous government, taking responsibility as the government of this country and that's remarkable.

There may be a fruitful dialogue with the IMF and donors. I think donors should help the government solving the problems and helping the government doing the right thing. The State shall establish legislative measures and enforcement mechanisms to be followed so that this does not occur in the future. Now we also have to wait for the investigations to clarify responsibilities, without falling into a witch-hunt, but serenely; to learn and to evolve.

Does His Excellency think that the communication strategy the government is following abroad is the correct one?

I think it is. The communication strategy abroad is following a good path. I doubt one could do better. The fact that important figures like the prime minister and the finance minister, went to the United States to give explanations, or the president, who has gone to Europe to explain and speak with honesty, which demonstrates good will and a good communication strategy.

The country is currently in a complicated situation with the political and military conflict with RENAMO. His Excellency has experience as an architect of peace when you were president. What lessons have you learned in this regard, that can be useful in the current context?

What should be done is to look to the future of the country and seek to have an increasingly calm present in order to build a better future.

History’s lessons, not only for Mozambique, show us that war is never really won by anyone. There is a time when dialogue must prevail. In the Mozambique Independence War we had a victory, but we still had to go to a negotiation table to arrange the details of the independence, agreeing on a transition.

In the Destabilization War imposed by the minority-led and racist regimes of Southern Africa such as Zimbabwe (South Rhodesia at the time), we also put the need for dialogue on the front. The war was imposed after the failure of dialogue between the opposition forces in Zimbabwe and Ian Smith, which made the Frontline States supporting Zimbabwe's liberation struggle, Mozambique among them, decide to support the only recourse that Zimbabweans had; the armed struggle.

However, Mozambique also had a role in the diplomatic fight with the imposition of sanctions to Ian Smith’s regime, imposed by the United Nations (UN) and the Commonwealth. Our weapons were the pipeline, the railway line and the road that connected the port of Beira to Southern Rhodesia. This caused the Rhodesian regime to protest greatly, but the dialogue remained open between the racist regimes and the countries of the Frontline, culminating in the negotiations and the signing of the Lancaster House Agreements thanks to the United Nations mediators, the British and the Americans. There was war but also dialogue at the same time.

We took the initiative to establish a dialogue with the people who ran and supported the RENAMO in Rhodesia, Ken Flower, Head of Southern Rhodesia Security and the General of the Southern Rhodesian Army, Peter Walls, so people RENAMO could lay down their arms and return to Zimbabwe. In the end it could not be implemented: Flower wanted to implement it but Walls led RENAMO men to South Africa.

After Zimbabwe's independence in 1980 South Africa’s apartheid regime took the helm of the proxy war against us. From a war mainly focused in the center of the country, we also went to war in the north and south, against South African interests and its RENAMO proxies.

At that time, we tried to talk to the people leading RENAMO’s operations and with the apartheid regime. We thought that dialogue was necessary in view of the South African power and strength. The dialogue resulted in an agreement for which the apartheid regime itself, through the figure of South African Foreign Affairs Minister, was to mediate between what were at the time called rebels and us, but then RENAMO’s positions caused the dialogue to fail. Still, with indirect communications, we were tried to restart the dialogue, which culminated in the Rome Agreement of 1992.

The talks lasted two years as the war continued. RENAMO did not give its weapons up and the government could not let the people be massacred and the infrastructure destroyed, it had to defend itself; but negociate at the same time.

After signing the peace accords with RENAMO, the country had a huge task ahead in terms of reconstruction after the conflict and, at the same time, Mozambique was transitioning from a planned economy to a market economy, and from a single-party system to a multi-party one. How did this transition take place and which were the biggest obstacles and challenges that you had to face as president?

Peace is never complete when we look at all dimensions. There was no violence and we thought that peace would be consolidated in the process of economic and social development in which all the stakeholders were invited to participate.

Then, in the first multiparty elections in 1994, we made a campaign against ourselves, calling and promoting the ideals of freedom of choice and fighting the fear of the population to vote for our opponent, RENAMO, instead of using the fears of the population. It was a training for democracy.

Our main mission was national reconstruction. From 1975 to 1982 Mozambique progressed economically. In 1980, Samora Machel saw the following decade as the decade of victory over underdevelopment. We were moving forward but, because of the civil war, we lost two thirds of those gains made after independence. During the first five years following the democratic elections, we focused on the task of rebuilding what had been destroyed. We had previously encouraged the opening of the country to the market economy and I decided to be candidate in 1994 and to try to lead the country because I could not jump out of the leadership at that time with two new features: multi-party system and market economy.

Multiparty system was not something society was used to. In order to change to a multiparty system we held a popular consultation process, giving the necessary information to the population and the response of the people was that they did not need a multi-party system; Mozambique chose a single party system. Openness to a multi-party system was an anti-democratic decision that we imposed on the grounds that even if there is a majority of people asking for a single party system, the will of the minority that wants to form parties must prevails because it affects their fundamental rights and you cannot go against the rights of the minority. We cannot live on an island, and the world was going towards multi-party systems.

Proof that people were not asking for a multi-party system is that it took three years for new parties to appear. The Rome Agreements advocated that the elections should be held one year after the signing, but we had to wait because RENAMO was not ready and the UN had to stay in the country two years when they were supposed to stay only one.

We had to rebuild the country, combat poverty, consolidate peace and lay the foundations for development. So we intensified the relationship with the Bretton Woods institutions and the USA (from Samora Marchel’s visit in 1983 to Reagan, relations began to improve and we had access to development aid rather than humanitarian aid) and the EEC.

Peace requires development and development requires peace. Our job was to make both together at the same time. Consolidating peace by creating development.

The Joaquim Chissano Foundation's mission is to increase the level and quality of economic, social and cultural development of Mozambicans. What has the Foundation mainly contributed to this mission?

Peace cannot be achieved only with words. When my colleagues gave me the idea of creating a foundation, I accepted and we talked about what its focus should be. We decided it should be peace, which involves the development of the people. Peace cannot be made with empty stomachs.

The fight against hunger is vital. The government has a comprehensive plan, but we think the forces of civil society should complete the task of the government working with communities to, next to them, try to promote a culture of peace in the way of living and organizing. We combine peace with development.

When people are together they also have a spiritual basis, not in the religious but in the cultural sense, that unites them. The various cultural facets of our country create a Mozambican culture that is how Mozambicans are, it’s what identifies us. In the Foundation, we want to add to this culture the peace dimension. Which is inseparable from national unity, solidarity, Mozambican identity and moçambicanidade (Mozambican-hood).

In this country there are several tribes, ethnic groups, regions, races but we built the feeling of being part of this country from the Mozambican Liberation War against Portugal. As in the USA, where there are many people from other countries, but they identify themselves as Americans, we, during the National Liberation War, created Mozambique.

Not long ago I was at a convention of war veterans, with people from all over the country, but they identified themselves as Mozambicans, they all shared this common identity that we want to promote.

We also work with children a lot, for them to be people of peace, fostering contact with other peoples from other cultures, such as the Friends of the Planet project, through the possibilities that new technologies provide us with.

But also adults have projects to promote other aspects of development such as in agriculture, an area which has huge potential, helping in the training of farmers in management, production, processing, the addition of value to their products, marketing, and so on.

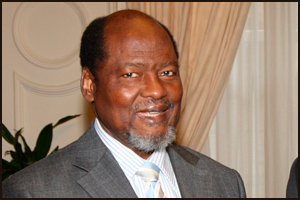

His Excellency has been recognized with several international awards and, as president for 19 years, ushered in peace, democracy and openness of the economy. As former president you have also struggled for equality between men and women and against all forms of discrimination. Given your track record, how you would like to be remembered?

I would like to be remembered above all as a fighter in the struggle for the liberation of the country. That is the first thing. I would very much like for it not to be forgotten. But I could also be remembered for having directed the country's peace process after these years of fighting between brothers, though caused by external forces, and for having introduced the reforms in the political and economic fields in our country by opening it to the market economy and, at the political level, to a multi-party democracy and, as a result, be able to facilitate the reconstruction of the country.

Finally, what is the message that His Excellency wants to convey to potential investors and readers of Harvard Business Review in relation to Mozambique?

I could make an appeal to all friends of Mozambique in the past to continue to be friends of Mozambique now. It is not as a consequence of a mistake that they should distance themselves from us, on the contrary, they should show solidarity with Mozambique now, to help us correct any mistake or obstacle in the continuation of our progress. Mozambique has all the conditions to contribute to the progress of the world and humanity. We can improve together.