OIL - STILL FUELING THE FUTURE

OIL - STILL FUELING THE FUTURE |

Despite the Russian government intention to diversify

the economy, Oil is and will for some time to

come remain the jewel in the crown of Russia's

economic development. In fact, oil was one of

the determining factors in the country's recovery

from its 1998 financial crisis. True, plans have

been put forward in Russia to diversify the economy

away from the energy (oil) sector by shifting

the tax burden from manufacturers to extractors

by pumping up taxes on energy exports, but for

the time being this is future talk.

In 2002, energy resources made up 56.4 percent

of Russia's overall exports to Western countries.

Russia is today's second-largest exporter of oil

in the world. Total revenues from oil exports

amount to no less than one quarter of Russian

government revenues. Russian hydrocarbon production

facilities such as the one in the Tyumen Oblast

in West-Siberia, the oil fields in the Caspian

Sea or the Far Eastern reserves are only a stone

throw away from both the European and Asian markets.

And, the United States' move to upgrade Russia

from a second-rated player to vital ally surely

has more than a few political reasons. True, Russia

currently only accounts for a pitying 0.77% of

US oil imports, but this is about to change. A

start was made with the Russia-US "energy

dialogue" launched in May 2002 when US President

George Bush visited Moscow. The US is starting

to realise that, next to the Middle Eastern huge,

but increasingly unstable powerhouses, Russia

has more oil reserves than any country or region

can compare with. Russian oil reserves are estimated

at 49-55 billion barrels or 9% of the world's

proven oil reserves.

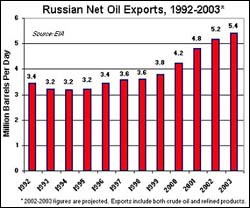

In fact, quarter one of 2002 saw for the first

time since the 1980s, Russia overtaking Saudi-Arabia

to regain its position as the world's leading

oil producer. This however did not come naturally.

During the 1990's, Russia's oil future looked

bleakish with production volumes plummeting down

from nine to six million barrels a day. With a

steady stream of oil orders from the formerly

planned economy coming to a standstill, reform

of the industry was inescapable. The aim of the

reform was the privatization of completely inefficient

state-owned enterprises. This reform was accompanied

by the much-needed change of the industry's structure.

Several large, vertically integrated oil companies,

like Yukos,

LUKoil, Sibneft and Tyumen Oil Co. (or TNK), now

dominate an industry formerly ruled by the Soviet

Ministry of the Oil Industry.

Important was the separation of pipeline transport

from potentially competitive activities, such

as the extraction, processing and marketing of

oil and oil products. In practice, there is room

for competition only in the export of Russian

oil and oil products. Exports to foreign markets

are somewhat restrained. Today, Transneft is the

state-owned oil distribution monopoly. The company

has full control over pipeline transportation

in Russia, but not for long if it is up to Russia's

overtly productive and profitable oil giants.

Very much against the will of OPEC, the non-member

Russia's oil output is growing for the fifth straight

year. The World Bank estimates that $6 billion

to $10 billion in annual investment is needed

to increase oil production to the levels Russia's

energy policy foresees by 2010. Domestic oil producers

cannot be expected to pitch in more than 50% of

this amount, which did not prevent Russia from

increasing its oil output by 9.9% in 2002 and

the expected 10 per cent in 2003 from the current

level of 8 million bpd. 4 million bpd is exported

abroad through pipelines, ports, rail and other

routes. Yukos Oil, which overtook its main rival

LUKoil as No.1 Russian oil producer for the first

time in monthly crude production, plans to boost

exports by 40% in 2003, including to China and

the US.

|

Contrary to their Middle Eastern rivals, however,

pipeline bottlenecks are hampering Russian producers'

oil export and causing cost increases. Transneft

can only handle 3.5 million bpd and is not always

willing to serve the producers' needs. The oil

majors have to find alternative routes to lucrative

western markets. Indeed, limited export facilities

with an unbridled desire to boost exports to foreign

markets are resulting in rising capital expenditures

by the Russian oil majors. These expenses translate

into investments in infrastructure and transportation,

like the LUKoil-Conoco project to transport crude

oil through the Arctic waters and Yukos' plan

to build pipelines to China and through the Balkans

to the Adriatic Sea.

Mikhail Khodorkovsky, CEO

of Yukos Oil

Mikhail

Khodorkovsky, CEO of the immensely successful

Yukos Oil, stresses, "…the key component

for any Russian company remains transportation

costs and markets. Our marketing arm is able to

maintain exports at a high level, and the fact

that we have opted for a strategy of negotiating

long term contracts has given us the opportunity

to acquire some very attractive segments of the

market".

In any case, despite government imposed export

tariffs and cuts and so on, the advantages of

exports are too high for Russian exporters. If

the truth be told, Russia's oil industry benefited

substantially from this crisis, which saw the

devaluation of the rouble and consequently also

a substantial lowering of production costs. The

difference between domestic and export prices

- the fact that Russian oil prices are indeed

just over half of the global market prices - plus

the guarantee of hard currency payment for exports

are too tempting. Either they will export crude

or refined oil products. According to Riabov,

General Director of the Oil Refinery Association,

it is important to process domestically, "and

then export finished products in order to attract

foreign currency into the country. This is why

our tax legislation is now being improved to make

it the same for domestic as well as foreign investors

and to have a guarantee for raised funds."

How attractive then is the Russian oil industry

to foreign investors? Well, certainly interesting

enough for BP to strike a record $6.75 billion

deal with TNK in February 2003. The deal created

a global top 10 oil producer, valued at $18.1

billion. This landmark investment of the British

giant, equalling some 1.5% of Russia's GDP, into

Russian oil could easily ignite a rush of other

global oil majors into the Russian Federation.

Up until the BP/TNK deal was signed and brought

serious competition to the Russian market (which

had been dominated by LUKoil and Yukos), though,

the level of direct investment in Russia's oil

industry had been a mere $4.5 billion and much

below what is needed for Russia to reach its future

production objectives. In fact, this capital was

primarily invested in high-risk and pricey offshore

projects in the pacific and the Caspian Pipeline

Consortium, which aims to connect Caspian fields

to Black Sea ports. Russia's ailing service sector

does provide opportunities to foreign technology,

equipment and service providers. Some large international

service companies (e.g. Schlumberger, Halliburton,

Parker Drilling, Pride Foralsol) have recently

signed major contracts with Russian oil majors.

Still, a more interesting Russian oil investment

climate will have to include a still missing fully

transparent legal infrastructure, including a

'production-sharing agreement' law.

|